(A Critical Examination in the Light of Qaradawi and Contemporary Discourse)

Introduction

IntroductionIn Islamic political thought, an intriguing yet controversial concept emerges: Murūna (مرونة). Literally translating to “flexibility” or “adaptability,” it appears appealing on the surface, suggesting a way to adapt religious principles to real-life circumstances without rigid adherence to rules.In everyday Arabic usage, Murūna innocently denotes mere adaptation. However, when examined in the writings of influential Islamic thinkers like Yusuf al-Qaradawi, it takes on a highly strategic form—a tool for infiltrating societies, temporarily bypassing religious prohibitions, and molding external behavior while preserving internal ideological rigidity.This raises profound questions:

- Is this truly religious tolerance, or a calculated strategic deception?

- Is it a means to “ease the practice of faith,” or a weapon of “political Islam”?

Al-Qaradawi’s Interpretation of Murūna

The concept of Murūna is most systematically articulated by Yusuf al-Qaradawi (1926–2022), one of the most prominent ideologues of the Muslim Brotherhood.In his renowned book Priorities of the Islamic Movement in the Coming Phase (Fiqh al-Awlawiyyat), he argues that:

- Muslims should abandon rigid literalism (word-for-word interpretation) and demonstrate flexibility in practice.

- Through this Murūna, Muslims can seamlessly integrate into modern societies.

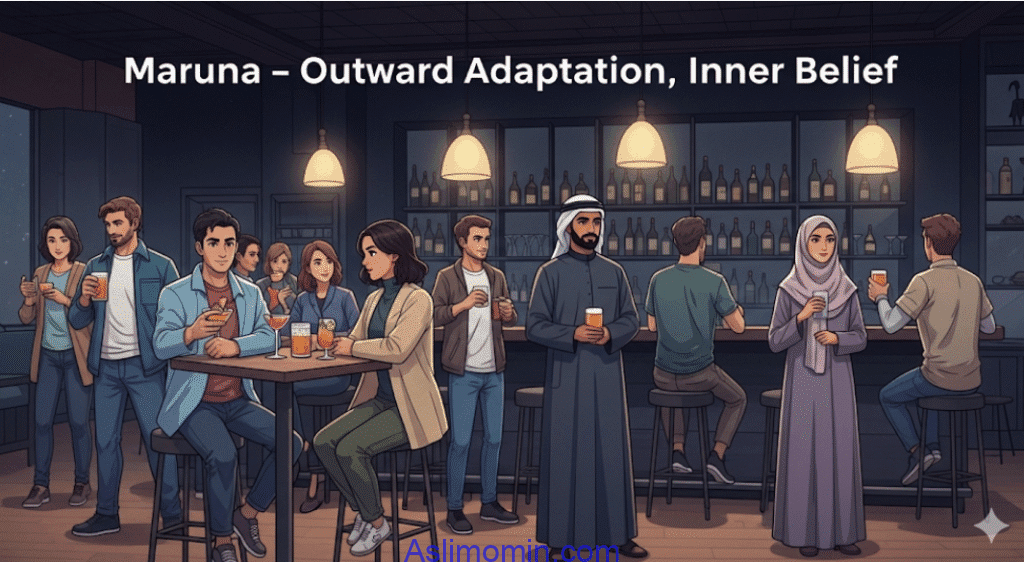

According to Qaradawi, this strategy allows Muslims to adapt in situations where strict adherence to Sharia is challenging. Many analysts believe he permits activists in da’wah (propagation) and the Islamic movement to participate in places typically deemed haram (forbidden), such as clubs or venues serving alcohol, provided the intent is to serve Islam.This idea seemingly stems from the Quranic principle of darūra (necessity), but it extends beyond mere survival to strategic infiltration. In effect, Qaradawi effectively alters Sharia boundaries: what is normally haram can be temporarily deemed permissible if it advances Islamic objectives.

What Critics Say

Modern Islamic apologists present Murūna as evidence of Islam’s practicality and adaptability to the times. They argue it provides essential cultural flexibility for da’wah in multicultural or secular countries.Yet, this is where the controversy ignites.

Jonathan D. Halevi (Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, 2009) describes Murūna as a “camouflage doctrine.” Muslims appear “moderate” and “modern” on the outside while advancing an Islamic agenda from within.

Caroline Fourest, in Brother Tariq (2008), contends that Qaradawi’s teachings grant Muslims a “license” for Islamic propagation. Per Fourest, Muslims may frequent clubs, adopt modern lifestyles, and even visit alcohol-serving venues to feign social integration—while the true purpose remains da’wah.

Lorenzo Vidino, in The New Muslim Brotherhood in the West (2010), asserts that Murūna is framed in the language of integration, but its ultimate goal is gradual Islamization—the slow reshaping of society in an Islamic mold.

Patrick Sookhdeo (2008) labels it “strategic deception,” where outward displays of liberalism and tolerance mask the inner pursuit of power and Sharia dominance.

Parallels with Taqiyya and Kitmān

Several scholars draw parallels between Murūna and older doctrines like taqiyya (concealing faith under duress) and kitmān (partial concealment of truth).

The key difference: Taqiyya is defensive, used for self-preservation or avoiding persecution.In contrast, Murūna is offensive and strategic: temporary adaptation to infiltrate non-Muslim societies and advance da’wah.

Moral Duplicity

Does this teaching not encourage a “double standard” in ethics?

- A public code of conduct (feigned liberalism for non-Muslims),

- And a private code (strict Sharia for one’s own community)?

Practical Examples

In pluralistic democracies—such as India, Europe, or America—Murūna manifests in various forms:

- Political infiltration: Joining secular parties or institutions without abandoning Islamic ideology.

- Social camouflage: Appearing liberal, tolerant, and integrated, while harboring long-term plans for Islamization.

- Selective morality: Engaging in acts otherwise considered sinful (e.g., shaking hands with the opposite sex or participating in non-Muslim festivals), provided they advance da’wah.

This explains why Muslim Brotherhood affiliates often engage in interfaith dialogues, position themselves as a “modern Muslim voice,” and advocate for integration and coexistence. Critics, however, question:If Murūna permits temporarily sidestepping divine prohibitions for political gain, what remains of the true meaning of divine law?Is this merely the soft face of political Islam, paving the way for future Sharia implementation?

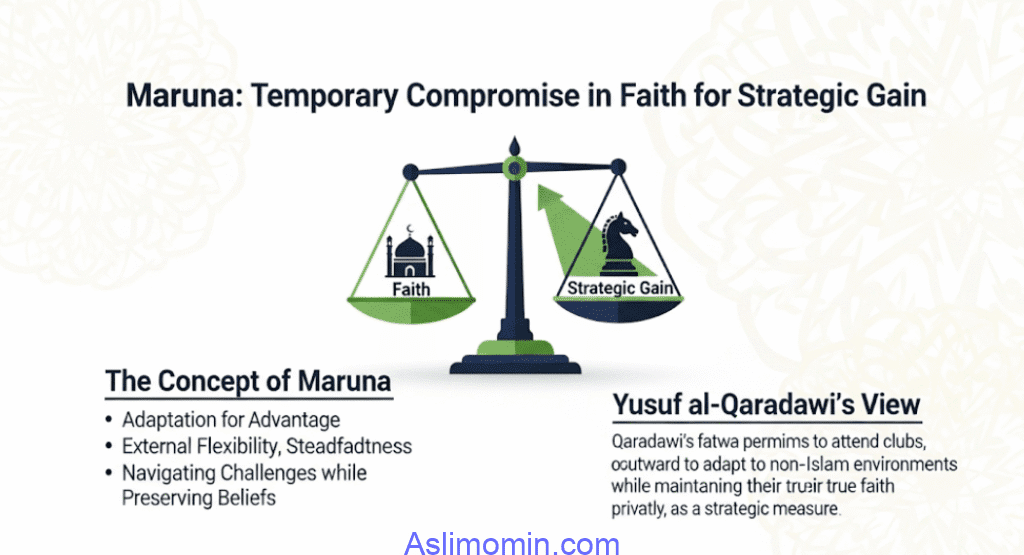

Permissibility of Strategic Sin?

A major concern arises:Does Murūna imply that Muslims can temporarily loosen Sharia rules for propagation or survival?Examples:

- Entering a non-Muslim society’s alcohol-serving club if it aids da’wah is deemed justifiable.

- Adopting modern attire or social mixing is temporarily tolerated if it secures societal acceptance.

Critics decry this as “licensing sin for propagation.”

Fundamental Questions

If Sharia observance is relaxed only when Muslims are a minority—and enforced strictly once they become a majority—is this ethically and religiously justifiable?Is Murūna truly a way to “ease the faith,” or a strategy for living a “double life in the name of religion”?If Islam is divine truth, does it truly require such camouflage and strategic flexibility for its propagation and expansion?

Conclusion (An Open Question, Not a Final Verdict)

As outlined in Qaradawi’s Fiqh al-Awlawiyyat, Murūna is not mere flexibility but a profound moral paradox—the temporary suspension of Sharia prohibitions in the name of Islamic dominance.For supporters, it is a pragmatic policy for surviving in modern societies.For critics, it is institutionalized hypocrisy and strategic deception, laying the groundwork for Sharia supremacy in pluralistic societies over the long term.

The real question remains:

Is Murūna religious flexibility, or a new form of Islamic politics?

📢 Did you find this article useful?

🙏 Support our work by clicking here.

📌 References (Secondary Sources)

- Yusuf al-Qaradawi, Fiqh al-Awlawiyyat (Priorities of the Islamic Movement in the Coming Phase).

- Lorenzo Vidino, The New Muslim Brotherhood in the West. Columbia University Press, 2010.

- Patrick Sookhdeo, Understanding Islamic Terrorism. Isaac Publishing, 2004.

- Patrick Poole, “The Muruna Deception,” Counterterrorism Blog (2007).