Introduction

Islamic tradition claims that the religion began in Mecca, but historical and epigraphic evidence suggests that its roots lay deeply in the monotheistic traditions of Yemen and Habasha (Ethiopia).

1. “Rahman” — God of Yemen, not an Islamic invention

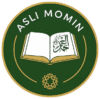

The Qur’an (25:60) states:

“And when it is said to them, ‘Prostrate yourselves before the Rahman,’ they say, ‘What is Rahman?’”

Several classical exegetes (Ibn Kathir, Zamakhshari, Tabari, among others) explain that when Muhammad began to use the title “Rahman,” the Meccans were puzzled and responded:

“We do not know Rahman; we only know Allah.”

This fact makes it clear that the term “Rahman” was already in circulation before Islam and had its roots in Yemen’s monotheistic tradition. Muhammad’s adoption of the title was not sudden but rather an extension of an already existing religious vocabulary and divine tradition.

2. “Rahman” and “Muhammad” in Yemeni Inscriptions

Marib Dam and the Qahtanite–Adnanite Division

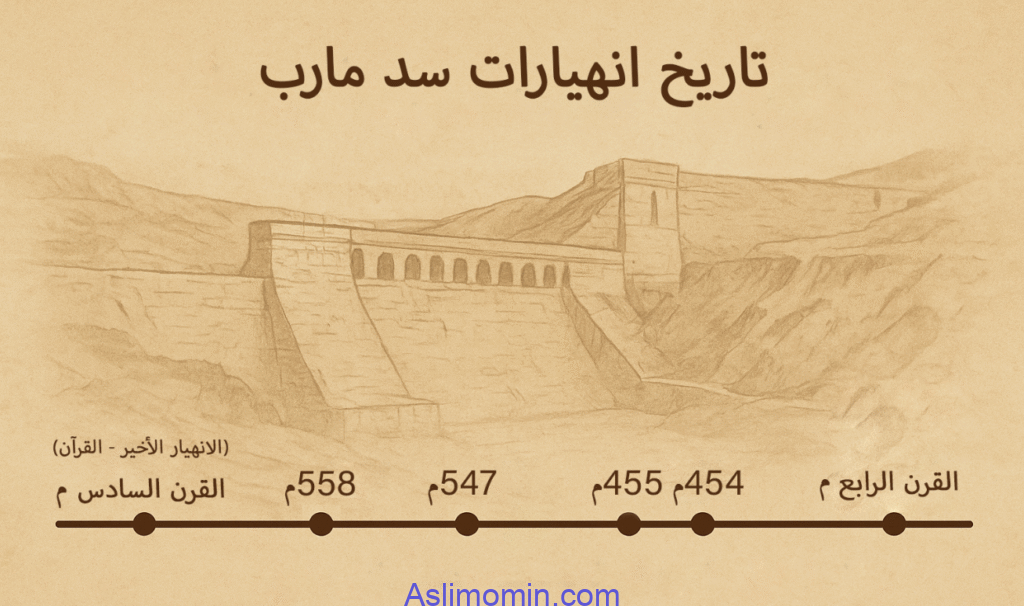

Southern Arabia (Yemen) was in antiquity the center of a prosperous civilization. The Marib Dam (8th century BCE) sustained agriculture and trade for centuries. However, its collapse caused the dispersal of the Qahtanite tribes across the Arabian Peninsula.

- Qahtanites (قحطاني, Qahtanite): Arabs whose original homeland was southern and southeastern Arabia—particularly Yemen.

- Adnanites (عدناني, Adnanite): Arabs traced to the northern, western, and central parts of Arabia.

The Qahtanite tribes were divided into two main branches: Himyar (Himyarites) and Kahlan.

According to Arab tradition, the Qahtanites were considered the “pure Arabs” (al-‘Arab al-‘Aribah), while the Adnanites were regarded as “Arabized Arabs” (al-‘Arab al-Musta‘ribah). Political and cultural rivalry between the two groups persisted from ancient times.

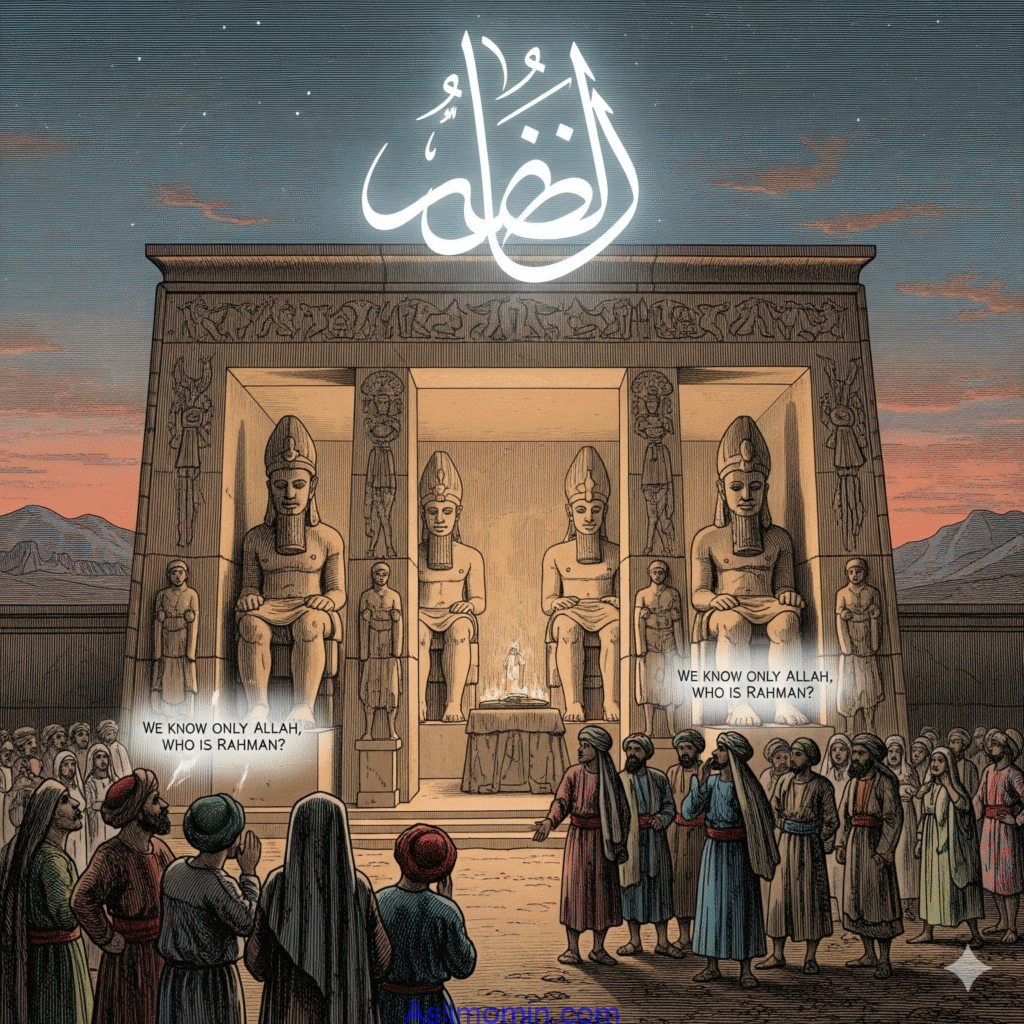

Collapse of the Marib Dam and Migration

The historian al-Isfahani (d. 961 CE) records that the dam at Marib collapsed about 400 years before the rise of Islam.

Yaqut al-Hamawi attributes the event to the period of Abyssinian rule.

South Arabian sources report that as early as 145 BCE, during wars between the Sabaean and Qatabanian states, cracks had appeared in the dam, laying the foundation for what the Qur’an refers to as the Sayl al-‘Arim (سَيْل ٱلْعَرِم, “the Flood of Arim”). This disaster also entered folklore and Arabic proverbial literature.

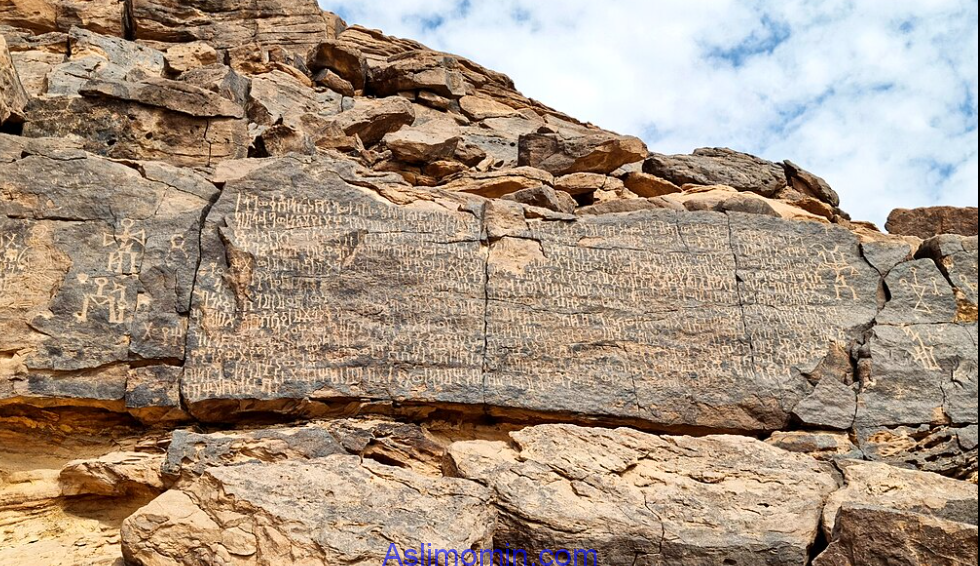

Epigraphic Evidence: “Rahman” and “Muhammad”

Inscriptions from Yemen and the Himyarite kingdom mention both “Rahman” and “Muhammad.” Key inscriptions include:

- CIH 541

- Ja 568

- Ry 515

- J 1028

Examples:

- “Bi-smi Raḥmānān” (“In the name of Rahman”)

- “Rb-hd b-Mhmd”

Here, Rahmanan (𐩧𐩢𐩣𐩬𐩬, rḥmnn) means “the Merciful,” used as an epithet for God. Between the 4th and 6th centuries, it became the standard title for the monotheistic deity in South Arabia. Scholars believe its earlier source lay in Syria.

After the Himyarite kingdom adopted Judaism, “Rahmanan” was worshiped as the official God. Initially, its use may have reflected monolatry (exclusive worship of one deity without denying others), but under 6th-century Christian influence it evolved into strict monotheism.

These inscriptions also contain the term “Muhammad” or “mhm’t,” used not as a personal name but as a religious honorific title.

Dhu Nuwas and the Worship of Rahman

The Jewish Himyarite king Dhu Nuwas invoked “Rahman” in worship. This demonstrates that the name and the concept predated Islam and were part of the monotheistic religious-cultural heritage of Yemen.

Summary

“Rahman” and “Muhammad” were not Islamic inventions but elements of Yemen’s pre-Islamic religious-cultural vocabulary. The Qur’anic account of the Meccans’ objection to the term “Rahman” is evidence that the name was borrowed from an external (Yemeni) tradition. Epigraphic records prove that Islam’s roots were not in Mecca but in the monotheistic movements of Yemen.

3. Collapse of the Marib Dam and the Settlement of Mecca

In the late 5th century CE, the collapse of the Marib Dam (سد مأرب, Sadd Ma’rib) forced large populations from Yemen to migrate toward Mecca and Medina.

The Qur’an (34:15–17) refers to the people of Saba (Qawm Sabaʾ) and mentions the Sayl al-ʿArim (سَيْل ٱلْعَرِم, “the Flood of Arim”), which is widely understood to allude to this historical disaster.

Before this displacement, Mecca is not mentioned in any ancient texts, maps, or records. Only after the arrival of the Qahtanite migrants from Yemen did Mecca, Medina, and the surrounding regions become settled. This explains why Mecca begins to appear in historical sources only from the 6th–7th centuries onward.

Preference for Yemen and Syria in Prophetic Prayer

Hadith literature also reflects this historical-cultural orientation, showing Muhammad’s special affection for Yemen over central Arabia.

In Sahih al-Bukhari (Kitab al-Fitan, Hadith 7094), Abdullah ibn Umar narrates:

The Prophet (ﷺ) said:

“O Allah! Bless us in our Syria; O Allah! Bless us in our Yemen.”

The people said: “And in our Najd (the eastern region of Arabia) as well.”

The Prophet replied:

“There will arise earthquakes and trials, and from there will emerge the horn of Satan.”

This narration appears repeatedly in Sahih Bukhari (1037, 1038, 3340, 7094), Sahih Muslim (1373a), and Musnad Ahmad (3/131).

“The people of Yemen have come to you; their hearts are soft and tender, their fiqh (religious understanding) is Yemeni, and their wisdom (insight) is Yemeni as well.”

This hadith indicates that Prophet Muhammad ﷺ himself acknowledged that his faith and the roots of Islam are connected to Yemen.

The fact that Mecca (Hijaz/Najd) was excluded from this prayer of blessing, while Yemen was given preference, reveals Muhammad’s emotional and cultural inclination toward Yemen rather than Mecca.

4. The Name of Mecca, the God Almaqah, and the Kaaba

Almaqah — National God of Saba

In pre-Islamic Yemen, the national deity of the Sabaeans was Almaqah (𐩱𐩡𐩣𐩤𐩠; Arabic: المقه, English: Almaqah), often associated with the moon. His main sanctuary was the Awam Temple (also known as Mahram Bilqis), which was active from the 7th century BCE until the 4th century CE.

When populations were displaced from Yemen, they carried this religious tradition northwards into the Hijaz. It is believed that this lunar deity was later worshiped under the name Hubal, and that his lunar symbol still survives in Islamic symbolism today.

The Kaaba and Almaqah’s Sanctuary

The altars of Almaqah closely resembled the structure of the Kaaba in both form and sacred function. Scholars suggest that the very name “Mecca” may have derived from Almaqah, introduced by the Yemeni migrants.

Thus, the collapse of the Marib Dam, the migration of Yemeni tribes, and the cult of Almaqah collectively laid the religious-cultural foundation of Mecca and the Kaaba long before the rise of Islam.

5. The Architecture of the Kaaba — A Yemeni Tradition

Ancient South Arabian temples had distinct architectural features:

- They were often built in a rectangular or square form.

- Their entrances usually faced south.

The Kaaba itself is a cuboid structure, which originally served as a pilgrimage site for Yemeni worshipers.

One corner of the Kaaba is still called the Rukn al-Yamani (the “Yemeni Corner”), a direct and visible reminder of this Yemeni heritage.

The historian al-Azraqi, in his Akhbar al-Makkah, explicitly notes:

“The Kaaba was not built by Abraham, but rather by the Amalekites and the Jurhum (people from Yemen).”

6. Import of Religious Concepts

Many of Islam’s central religious ideas were not original but pre-existed in Yemen, Abyssinia (Ethiopia), and the Jewish–Christian traditions.

- “al-Rahman” — found in Himyarite Jewish inscriptions and South Arabian epigraphy.

- “Jannah” (Paradise), “Hur,” “Jahannum” (Hell) — derived from Judeo-Christian traditions and Gospel-based narratives circulating in Abyssinia.

The decision to make the Kaaba the spiritual center of Islam was also strategic:

- Its structure already existed.

- By embedding it into a framework of “Sacred History,” it became easier to craft a new religious narrative around an established site of devotion.

7. Qur’anic References to the People of Tubbaʿ and the People of Saba

(a) The People of Tubbaʿ (قَوْمُ تُبَّعٍ)

The Qur’an (Surah Qaf 50:14) states:

“And the people of Tubbaʿ — all denied the messengers, so My punishment was justified against them.”

- Tubbaʿ was a royal title of the Himyarite kings of Yemen.

- His people lived in Hadramaut (حضرموت) and the surrounding regions.

- The word Hadramaut literally means “the city of death.”

Thus, “the People of Tubbaʿ” is a direct Qur’anic reference to Yemen and its Himyarite subjects.

(b) The People of Saba (قوم سبأ)

The Qur’an (Surah Saba 34:15) records:

“Indeed, there was for the people of Saba a sign in their homeland: two gardens, one to the right and one to the left…”

- Saba (Sheba) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom, with its capital at Marib.

- At times, it was part of the broader Hadramaut domain.

This Qur’anic reference acknowledges the wealth, prosperity, and eventual decline of Yemen’s ancient civilization.

Conclusion:

These passages show that many Islamic narratives and theological motifs were direct borrowings from Yemeni and Abyssinian traditions, later reframed into a “Meccan history.”

8. Bir Barhout — The Well of Hell

Location:

Bir Barhout is located in Hadramaut (literally “City of Death”) in Yemen. It is a mysterious well long regarded in Arabic folklore and Islamic tradition as the Well of Hell.

Islamic and Folkloric Beliefs

- Abode of Jinn:

According to tradition, it is the dwelling place of Ashrar al-Jinn (evil jinn). Strange sounds are said to emanate from it, and locals avoid approaching it at night. - Refuge of Evil Souls:

Ibn Abi Dunya (Kitab al-Qubur) wrote: “Barhout is the place where the worst souls are kept.”

Imam al-Awzaʿi taught:

“The soul of the sinner is cast into Barhout after death.” - Hadith and Reports:

- “From Barhout comes a foul stench; it is one of the gates of Hell.” (al-Azraqi, Akhbar al-Makkah)

- “In Barhout there is no water, only darkness and demonic spirits.” (Sufi traditions)

- Some hadith state: “The most evil souls will be thrown into Barhout.”

Sufi Perspective

- Many Sufis described it as a spiritual warning and a prison for trapped souls.

- Al-Qurtubi (Tafsir al-Qurtubi) affirmed it as a fortress of wicked spirits.

Mentions by Historians

- Historians such as Ibn Khallikan and Ibn Battuta recorded descriptions of the Barhout well.

Modern Exploration

- Studies by the Yemen Geological Survey (YGS), Oman Cave Exploration Team (OCET), and UNESCO Cultural Heritage Reports have documented the site.

- In 2021, Omani speleologists descended into the well for the first time and found:

- Depth: approx. 112 meters

- Limestone walls

- No evidence of supernatural forces or gases

- A strange foul odor confirmed

Conclusion

Bir Barhout stands at the intersection of religion, folklore, and science.

- In Islamic tradition, it was branded as a gate of Hell.

- In modern geology, it is identified as a natural limestone sinkhole.

Yet, the lore surrounding Barhout strongly suggests that this site of Hadramaut served as one of the sources of Islamic ideas about Jahannum, fallen spirits, and the dwelling of jinn.

9. Reconstruction of the Kaaba — Materials from Yemen and Egypt

Historical Event (605 CE):

Before Muhammad’s prophethood, the Kaaba was damaged by a flood. At the same time, a ship carrying timber and stones from Yemen and Egypt was wrecked near the port of Jeddah. Its materials were salvaged and used for the reconstruction of the Kaaba.

Primary Sources:

- Ibn Ishaq, Sirat Rasul Allah (trans. A. Guillaume, p. 85–86):

“A Greek merchant named Baqūm, who was bringing wood from Egypt, had his ship wrecked near Jeddah. The Quraysh used that timber for rebuilding the Kaaba and engaged Baqūm, a Coptic Christian craftsman, in the construction.” - Al-Tabari, Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk:

“When the Kaaba was destroyed by the flood, the Quraysh decided to rebuild it. A Byzantine ship was wrecked at Jeddah. Its timber was purchased, and the Coptic craftsman Baqūm was summoned.”

Significance:

During this reconstruction, a dispute arose about who should place the Black Stone (Hajr al-Aswad) into its position. Muhammad devised a clever solution: he placed the stone on a cloth and had all tribal leaders lift it together, while he himself placed it in the wall.

This event not only highlighted his diplomatic skill but also underscored the Kaaba’s connection with Yemen and Egypt, both in structure and material.

10. The Black Stone (Hajr al-Aswad) — A Symbol of Yemeni Tradition?

Location: Embedded in the southeastern corner of the Kaaba, the Black Stone is oval in shape. Hadiths describe it as “sent down from Paradise,” and pilgrims are encouraged to kiss, touch, or point toward it during Hajj.

Was it brought from Yemen?

There is no direct proof, but circumstantial evidence links it with Yemeni practices:

- Stone Worship in Yemen:

– The kingdoms of Himyar, Saba, and Qataban practiced veneration of sacred stones, meteorites, and unique rocks.

– Such stones were treated as representations of deities, often placed in sanctuaries (bayt) or sacred stations (maqam). - Parallels with Sabaean Tradition:

– In Marib and Saba, square temples and sacred pillars were common.

– Sacred stones symbolized divine presence.

– The cuboid shape of the Kaaba and the centrality of the Black Stone may have been influenced by these traditions. - Pre-Islamic Mecca:

– Ibn Ishaq, al-Zuhri, and Ibn Hisham record that Quraysh and other tribes already revered the Black Stone.

– They kissed it, offered sacrifices, and regarded it as a cosmic talisman.

– It was sometimes described as the “Eye of God” or a protective amulet.

Conclusion:

The Black Stone was revered long before Islam. Muhammad reinterpreted its meaning within a monotheistic framework. While direct origin from Yemen cannot be proven, the similarities between Yemeni sacred stone traditions and the Kaaba’s rituals suggest a deep cultural connection.

11. Jurhum — The Yemeni Foundation of Mecca

Islamic tradition holds that after Abraham and Ishmael, the first tribe to settle in Mecca was the Jurhum, a Qahtanite (southern Arabian) people from Yemen.

- They assumed guardianship of the Kaaba and maintained its rituals.

- They supported Hagar and Ishmael, protected wells and sacred stones, and introduced idol worship into the Kaaba.

- They effectively transformed Mecca into a religious sanctuary.

Was Mecca historically invisible?

Before the 6th century CE, “Mecca” is absent from Greco-Roman, Persian, and Indian maps, travelogues, or records.

Critical Historians:

- Patricia Crone (Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam):

Mecca was not a major trade hub; its prominence is a later Islamic construction. - Tom Holland (In the Shadow of the Sword):

Early Islam may have developed in northern Arabia or Syria, not Mecca. - Dan Gibson (Quranic Geography):

Islam originated in Petra, since the earliest mosques faced Petra rather than Mecca.

Special Question

Why did the Prophet pray for Yemen and Syria, but not for Najd (the Meccan region)?

- Yemen and Abyssinia (Ethiopia) were seen as fertile, civilized, and divinely blessed regions. This shows the Prophet’s cultural and emotional affinity with them.

- In contrast, about Najd he said: “From there will arise earthquakes and tribulations, and from there will emerge the horn of Satan.”

(Sahih Bukhari 7094, 1037; Sahih Muslim 1373a)

Final Conclusion

- “Al-Rahman” was borrowed from Yemeni religious tradition.

- “Muhammad” existed as a pre-Islamic honorific.

- Mecca was likely settled by migrants from Marib after the dam collapse.

- The Kaaba’s design and the Black Stone’s sanctity show continuity with Yemeni practices.

In essence:

“Islam was not born purely in Mecca, but inherited the monotheistic traditions of Yemen and Abyssinia. Muhammad reworked these traditions within a Meccan framework for political purposes.”

📢 Did you find this article useful?

🙏 Support our work by clicking here.